How to Make a Board Game (a step-by-step guide)

I’ve written hundreds of articles over the years. I’ve gone into how to come up with game ideas, creating prototypes, playtesting (including unguided playtesting), and a whole lot more, but today’s article is going to tie everything together to help you make your own board game from scratch.

So, without further ado let’s get right into it.

Coming up with an idea

Now you may already have an idea for your game or perhaps you’re not sure what your game should be about. In either case, you’ll want to consider whether your idea is fresh and new, or just a retheme of another existing game.

While it’s totally fine to come up with new house rules or perhaps an expansion for an existing game that you love, which is often a new designer’s starting point, you’ll want the first game that you’re serious about making to have something innovative about it.

Ideas can come from just about anywhere. You might have an idea based on an existing board game, video game, movie, or even a scenario or a game name that you are trying to come up with a game around.

I wrote a whole article on how to come up with different ideas for a game, including using this randomizer.

Once you have your idea, it’s time to turn that into a prototype.

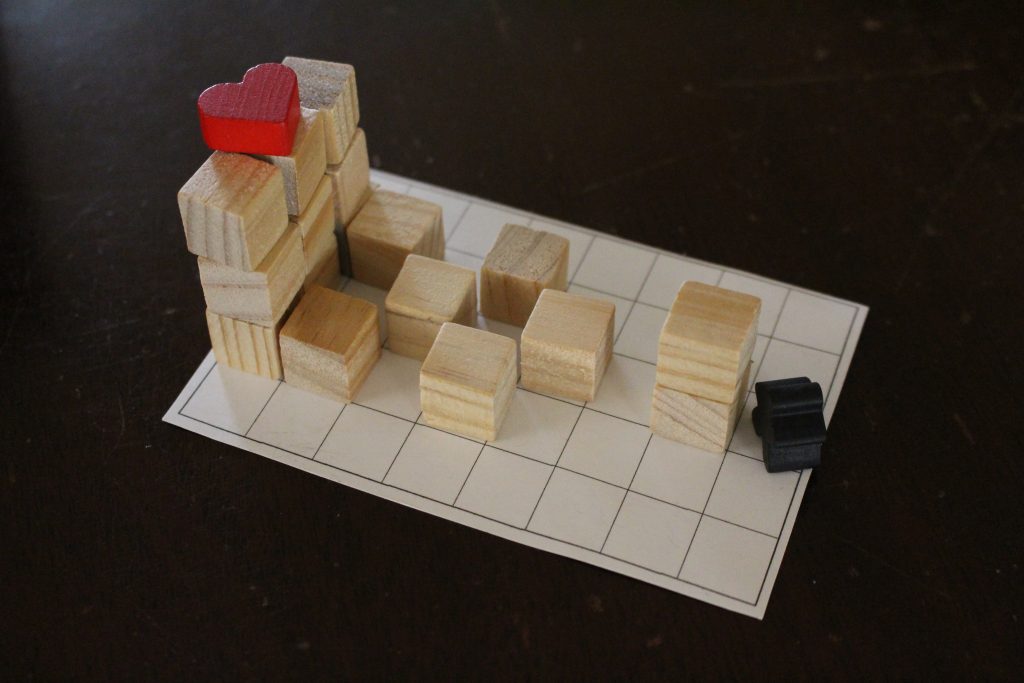

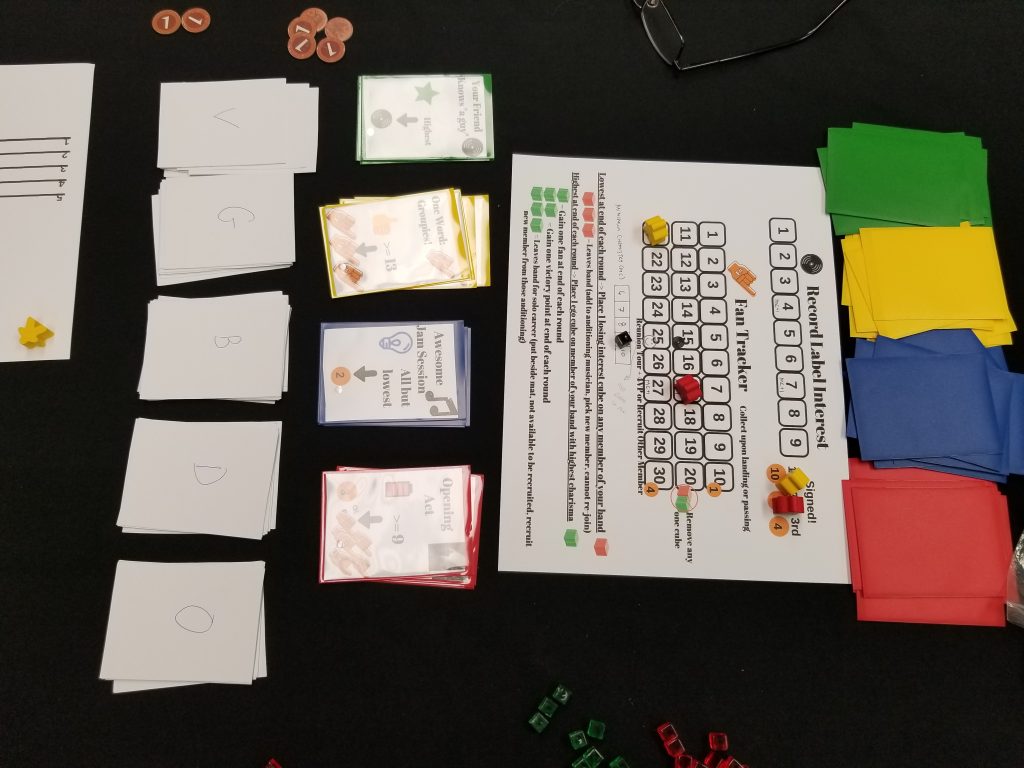

Creating your first prototype

This is often where most aspiring game designers get stuck. They have an idea, but don’t know what to do next to make a board game.

The easiest way to get going is to create a minimum viable prototype (MVP).

This means that rather than create the entire game you have in your head, which may consist of hundreds of cards with distinctive art, an elaborate board, and dozens of different components, you start with the minimal game you need to just get started.

What you’re doing is testing a concept. That means you don’t need to have everything fully in place.

The problem is, if you wait until you have everything you need and your game is absolutely perfect before you test it, you’ll never get your game to the table.

Don’t let perfection get in the way of what could be a really great game.

Instead, you’ve got to move forward if you want to make a board game. Create a minimal number of cards, a simple board, and grab whatever components you need from around the house or other games on your shelf, and let’s get this to the table fast!

Tools and components you can use

When you’re creating your MVP, use what you have available to you. Don’t worry about going to the store or ordering special components online to get it just right.

You probably have a computer, hopefully also a printer, along with paper, scissors, pens, and pencils. This is all you need to get started and make a board game.

You can make some simple cards from paper, card stock, blank playing cards, or index cards if you have these.

As a gamer, you probably have plenty of games on your shelf as well. Borrow whatever meeples, cubes, dice, tokens, money, or anything else you may need. You can always put these back in the original game box later.

While you can definitely create cards and other components by hand, there’s something to be said about being able to make multiple changes quickly. This is where computer software can help you to create and make iterations to cards and other components quickly.

Rather than changing the value and actions on multiple cards by hand, you can set things up to make one change that will be reflected throughout your entire deck.

There are plenty of computer programs you can use to create cards, tokens, boards, etc.

You can use any of the following programs to create most of what you need:

- Excel

- PowerPoint

- Canva

- InDesign

- Photoshop

- Nandeck

- Component Studio

- Various others

There isn’t necessarily a “best” program. However, you could say that the best program for you right now is the one you’ll use.

You can always learn Nandeck or InDesign another time. These programs will likely save you time down the road, but if all you know right now is PowerPoint, stick to this to make your first prototype.

Keep it simple. Don’t overcomplicate things. I can’t stress this enough.

Delaying the creation of your MVP because you don’t have the perfect wooden rutabagas or image of a sorcerer is just procrastination. These things are not needed to test your concept, which is all you’re doing at the stage.

You want to see if there is something fun and engaging about your idea, which will let you know whether it’s worth developing further. Imagine spending countless hours trying to put together the perfect prototype just to find out the idea is terrible or that it will never work.

Now imagine you’d spent 10 minutes creating a simple prototype to get this same information. This will allow you to make some quick changes to see if the game can work another way or decide to move on to your next idea quickly.

Again, you just need to go ahead and make a board game, not keep that idea stuck in your head until you’ve perfected it.

How to make a board game and playtest your game

Once you have a prototype for your game and you’ve tested it out by yourself to work out the initial kinks, it’s time to put your game in front of others and start gathering feedback by playtesting your game.

It’s important to make a distinction here between playing a game and playtesting a game. You play a game for enjoyment, social interaction, and a host of other reasons. However, when you’re playtesting a game, you’re essentially running an experiment. You have a hypothesis that things will work in a certain way, and you’re trying to validate whether or not that’s true.

That’s how you make a board game.

You’re trying to figure out first whether your game has potential (if it is fun and engaging) and then secondly trying to identify if the changes you’ve made have actually improved your game and made it more in alignment with the vision you have.

Outlining a clear vision for your game is also really important. You’ll receive feedback from playtesters that can vary quite a bit and will sometimes even be contradictory. Knowing what the vision is for your game will help you determine which feedback is helpful and what should be ignored (or at least not considered as highly).

To help you identify the vision for your game and get you moving ahead faster, make sure to check out my 10 Minute Board Game Design Blueprint.

It’s totally fine to start with friends and family or others you know, just to get the feel for your game and to determine what’s working well and what could be improved. But pretty soon you’ll want to start playtesting your game with people you don’t know.

Your friends and family won’t necessarily be able to give you the kind of unbiased feedback that you need in order to make your game the best it can be. While it may be hard to hear sometimes, you need critical feedback from people who can be honest with you.

You’ll playtest your game dozens if not 100 times or more as you iterate, make changes, and improve your game to the point where people ask you if they can buy a copy.

The important thing to remember here is everybody is trying to help you make your board game the best it can be. So, you have to get good at taking feedback and being able to filter this feedback to make your game better.

Taking feedback and improving your game

When you start to playtest your game, particularly with people you don’t know, you’ll get all sorts of feedback. You’ll have to get very used to people telling you what’s wrong with your game. This can be challenging when you’re first learning how to make a board game.

Rather than get defensive about things that people don’t like in your game, really listen to people to understand what their pain points are. If a comment comes up once, it may be something that only matters to that one player or only speaks to their own preferences and biases, but if you are hearing this comment consistently from multiple players, you know there’s definitely a problem you need to address.

What you’re really trying to identify are the problems, not the solutions (at least not right away). So, if a player suggests making a change, such as being able to attack other players to take their resources, ask them why they feel this way. Keep asking why until you get to the root of the issue. It could turn out that they feel that resources are too scarce in your game. That’s a valid concern. However, stealing from other players is only one possible solution to this problem.

It’s your job as a game designer to help playtesters identify the problems and then develop potential solutions yourself. That’s not to say that some playtesters won’t come up with some great ideas (I’ve received some amazing ideas from playtesters that greatly improved my games), but you shouldn’t rely on them for solutions.

Also, don’t take feedback personally. If players don’t like something in your game, this is no reflection of you as a person or as a game designer.

Remember, the role of playtesters is to help identify issues and make your game the best it can possibly be. That’s why playtesters are our most valuable resource and we need to treat them with dignity and respect. Even if you don’t agree with everything a playtester says, you want to thank them for sharing their thoughts and make sure they know they’ve been heard.

If a playtester doesn’t feel like you’re listening to them or if you get defensive about anything they suggest or bring up, they are far less likely to continue to share their thoughts openly or play another game of yours and offer helpful feedback. As a game designer, you must be able to receive this helpful feedback more than anything else.

Finalizing your game and what to do next

As you continue to work on your game and make it the best game it can be, the feedback you are receiving should change over time from identifying problems to merely suggestions that might make your game different, but not better.

If players are consistently asking to play your game again or wanting to buy a copy right then and there, you know you’re on the right track and it’s getting close to being ready to pitch to publishers or self-publish. Just make sure this is happening consistently. If issues are still being identified every other playtest, you’re not there.

The key is consistency.

If your game is feeling like it’s in the final stages, you’ll want to make sure to run unguided playtests to ensure players can play your game correctly and have a great experience with your game when you’re not around.

Then, you’ll have to make the decision about whether to pitch or self-publish. Or maybe you’re not interested in either of these options and rather just wanted to create a fun experience for others around you. That’s totally fine as well!

But if you’re looking to get your game out into the world, the approaches you can take are vastly different, and require completely unique skill sets, time commitments, and efforts.

I can’t tell you which path to choose. It’s really up to you and your situation as to which one is right for you. This can also change over time. Maybe you’ll pitch your first couple of games, then run your own Kickstarter campaign once you have more experience and a better understanding of the industry.

Final thoughts

I want to emphasize the importance of simply taking your idea and turning it into your first prototype. This is where it all starts. It’s also where it often ends for aspiring game designers.

Just getting your idea out of your head and onto the table is a huge step. Then, you can playtest your game and continue to tweak it and make it the best game it can be. That’s how to make a board game that people can’t wait to play.

If you’d like to move ahead even faster, make sure to check out my 10 Minute Board Game Design Blueprint.

This guide will help you outline your game and your vision, so that you can always be moving forward in the right direction.

2 comments

Jack Leen

Great article, Joe!!! Really helpful to get your most helpful thoughts all on one place.

Joe Slack

My pleasure, Jack!