How to create an amazing co-op game

I’ve created a number of co-op games since I first wrote this article many years back, some of which are progressing nicely and others that are currently collecting dust on a shelf, waiting for an inspiring idea to hit me. I even self-published a coop game I co-designed called 14 Frantic Minutes. So, I wanted to update this article, incorporating some new thoughts. I hope you find it helpful!

Sometimes it’s nice to take a break from beating your opponents and instead team up with them to accomplish something together. That’s why it’s great that so many fantastic cooperative (co-op) games are now available.

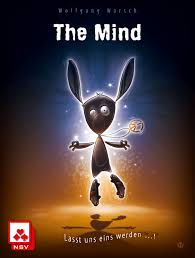

Some of the best-known and most loved co-ops are The Mind, Spirit Island, Hanabi, the Forbidden series (Forbidden Island, Forbidden Desert, Forbidden Sky, and Forbidden Jungle), and Pandemic, along with all its spin-offs and expansions.

There are many other fantastic co-op games as well that you might not have tried, such as Magic Maze, Escape: Curse of the Temple, and Flashpoint: Fire Rescue.

These are but a small representation of the many great co-op games now available.

But, as a game designer, how do you create an engaging co-op game that people love to play?

First, let’s explore what types of co-op games work well.

The two types of co-op games

Co-op games essentially pit players against the game. They must work together in order to win. Remember, there’s no “I” in team. Except if you’re French. Damn equipes! 😊

There’s a great podcast on the Board Game Design Lab featuring Peter C. Hayward, in which he goes into great detail about what he feels are the two main types of co-op games. He also goes into great detail on what makes them work so well and gives some great examples of each.

The first type is where players are constantly needing to put out fires. This could mean anything from the outbreaking viruses in Pandemic to the literal fires you must put out as you take on the role of firefighters in Flashpoint: Fire Rescue.

Players will have a specific goal they need to accomplish, but they can’t ignore the problems that surround them, which are present right from the start of the game. There’s one way to win and often multiple ways to lose. This gives the game a constant state of tension.

The second type involves limited communication. Some examples are The Mind and Hanabi.

In The Mind, players are dealt one card each from a deck of cards with the numbers one through 100. They simply have to play them in order. Simple, right? Except players can’t talk or give signals. Each round, players have one more card than the previous round, which makes the game more challenging as it progresses.

In Hanabi, players actually hold their cards facing outwards. So, you can see everyone else’s hand but not your own. You can only give clues as to a colour or a number, and players have to try to place their cards down in the proper order. This can get very tricky and may also require some memory work.

On the other hand, in Magic Maze and Escape: Curse of the Temple, players must act in real-time, working against the clock in order to try to win. Communication is limited here based on the speed at which you must move, but also by the rules, particularly in the case of Magic Maze, which allows you to move any of the 4 characters, but only in the direction(s) or manner showing on the tile in front of you. You’re not allowed to tell other players what they need to do. You can only signal them by placing a pawn in front of them, motioning for them to “do something.”

Both these game types can be very engaging. I’m going to focus more on the first, as it relates closely to the path that many co-op games take.

I also talk about these games in this article.

Making a challenging co-op game

As a designer, when you’re creating a co-op game, you want to look at what makes existing games so good, while adding your own unique spin.

We talked a bit about games that require you to constantly be putting out fires. The reason this is so effective is that you are always challenged to decide between moving closer to accomplishing your end goal, which is required to win and taking care of other problems, which is required in order not to lose. You ignore one at the peril of the other.

Another aspect that many of these great games provide is unique player powers. All characters can perform the same basic actions, however, they each have one or more special powers that only they can perform. This provides more replay value along with different variations and combinations you can try.

A few years ago, I was working on a co-op game tentatively titled Mystery Crew. In the game, you play members of a team, trying to capture a villain, who is roaming through a building, setting bombs as he goes. Your job is to capture him, but you must also defuse as many of the bombs as you can to avoid losing. Each character has a unique power, such as the defuser, who is more effective at taking care of the bombs, and the parkour pro, who can move about more easily.

So far, it sounds like a typical co-op game, right? It has all the same key elements, but nothing that really sets it apart.

I wanted to introduce something different that hasn’t been seen in other co-op games. Players are collecting clues, trying to identify who the villain is. However, if you don’t work fast enough, you may have to capture the villain before you know who it is for sure. So, even if you catch the villain, there’s still a risk that you can lose. This is something interesting that I hadn’t seen done in a co-op game previously.

I also had a great suggestion from a playtest that led me to setting the bombs up on timers. So, as time passes, each one ticks down and gets a little closer to going off. Certain cards in the villain’s deck also escalate the timers. These features definitely increase the tension!

Other considerations

One mechanic that you’ll often see used in cooperative games, including some already mentioned in this article is action points. On your turn, you will have a set number of action points that you can “spend” in order to take actions. Each individual action may cost one action point or more (some actions may also be free to take). Once you’ve used up all your action points, the next player takes their turn.

I’ve found that the way to really bring tension to a game using action points (this works really well both for co-op and competitive games) is to figure out how many actions would be ideal for players to accomplish something important on their turn. Then take away one action.

Having not quite enough actions to do everything you want to on your turn creates some great tension and tough decisions that a team has to weigh most turns. This is what you’re aiming for in a great co-op experience.

Also, one issue that often comes up in co-op games is the “alpha player.” This is the player that tells everyone else what they should do on their turn, often taking away the fun from other players. This is often considered a major problem in co-op games.

This is usually not an issue in the case of limited communication co-op games, as everyone is either under the same time constraints or they have limited information to work with. However, this phenomenon is often present in other co-ops.

Some suggest just not playing with people who try to take full control of a game. While this may work within your group of friends, you can’t control what happens at a convention or gaming group. Some argue that having a “leader” to help guide you through the first play of a game and offer helpful advice can be beneficial. So, it is more a matter of this happening outside the introduction to a game.

In my game14 Frantic Minutes, players are working real-time to complete circuits but can also only ever touch their own pieces. Players may make suggestions or ask someone to place a piece to see if it will help to make a connection and possibly solve the puzzle, but only the owner of that piece may touch it.

The “alpha player” issue may also be tackled by some great design choices. Make sure your game is challenging and there isn’t always one “best” move or decision. If you can create multiple ways for the team to go, this can lead to some good discussion of options and some real team-based decisions.

There are lots of different ways you can build on what already makes a great co-op game. You just have to add something new, whether it is an interesting mechanic or a fascinating theme that hasn’t been done before.

What’s your favourite co-op game? What makes it so fun or engaging?

Whether you’re making a co-op, competitive, or solo game, my FREE 10 Minute Board Game Design Blueprint will help guide you along the way.

4 comments

Bryce Brown

You missed a 3rd type of co-op game. Rescuing Robin Hood introduces the idea of solving the problem: “which of the good things do you want to unlock” as you prepare for finale ending. If your are considering creating a co-op game with a much more light-hearted feel than traditional co-op game you will definitely want to check out Rescuing Robin Hood at: https://castillogames.com/product/rescuing-robin-hood-2/

Joe Slack

That’s an interesting twist, Bryce! Thank you for sharing this.

The top 4 board game design articles from the past 4 years

[…] #4. How to Create an Amazing Co-op Game […]

Cooperative Board Game – How To Choose The Best For Your Family – AI Blog Articles

[…] How to create an amazing co-op game (discover the 2 types) […]